This last article — written after the rest of the book had gone to press — differs from the others inasmuch as it has not been published before. When the U.S. rocket Ranger VII was dispatched toward the Moon on 28 July 1964, there was considerable excitement everywhere, plus a general feeling that this time the programme of taking lunar photographs from close range would be carried through successfully. I made a fleeting appearance on television after News Extra on 29 July, and said that in my view the interesting problems likely to be solved were (1} whether the lunar seas were in fact deep dust-drifts, and (2) whether there were many small craterlets too tiny to be seen from Earth. I also said that I had the most serious doubts about the existence of dust, and that I expected large numbers of minor craterlets.

Half a dozen of the Ranger VII pictures had been sent across to us, so that we were able to put them on the screen less than twelve hours after they had been taken. It was all most interesting, and quite different from our abortive effort with Lunik IV over a year earlier! On that occasion (April 1963) we undertook a similar Sky at Night special as the Soviet probe, launched on 2 April, neared the Moon. The general consensus of opinion was that the Lunik would either make a 'soft landing' or else deposit a package of some kind on to the Moon. During the vital period I carried out a live transmission from Lime Grove; I had a telephone link with Moscow, a radio link with Jodrell Bank (where Colin Ronan was stationed, and where Professor Sir Bernard Lovell generously gave up some of his time to join in), and cameras fixed to the large telescopes at Edinburgh (with Dr Peter Fellgett commenting) and Patcham (where George Hole was in readiness). The idea was to get the latest news from Moscow, listen to the signals from Jodrell Bank, and observe the impact from Edinburgh and Patcham. What actually happened was that nobody in Moscow seemed to know anything, Jodrell Bank could not hear anything, it was raining in Edinburgh and cloudy at Patcham, and in any case Lunik IV missed the Moon by four thousand miles. The programme provided a perfect instance of the workings of Spode's Law.

At 13 hours 25 minutes on 31 July 1964 - that is to say, at 2.25 p.m. British Summer Time - the American rocket Ranger VII hit the Moon. For the previous quarter of an hour it had been transmitting pictures of the lunar surface taken from close range, and when the first photographs became available they proved to be of amazingly good quality. Features much too small to be visible from Earth were clearly shown, and several outstanding problems of the Moon were cleared up at once.

The success of Ranger VII ended almost six years of frustrating failure by the American scientists. The moon-shot programme had been started as long ago as 1958, but it had been dogged by ill-fortune from the outset, and the plan of setting a man on the lunar surface before the end of 1970 had begun to look very over- optimistic. Now, perhaps, the tide had turned.

The first United States moon-rockets were the Pioneers. Five were launched between 17 August 1958 and 3 March 1959, but with somewhat depressing results. The original vehicle reached i2i miles, but then its lower stage exploded and the flight came to a premature end. The next rocket, officially known as Pioneer I, was sent up on October 11 and reached an altitude of slightly over 70,000 miles, but then fell back to Earth and burned up in the atmosphere (at least, this was presumably its fate; no trace of it was ever found). Pioneer III, launched on 9 November, was a total failure, since its third stage failed to ignite, while the fourth attempt, made on 6 December, attained 66,200 miles before it too fell back. The last Pioneer, No. 4, went up on 3 March of the following year; it weighed 13 lb and passed within 37,000 miles of the Moon during the night of 4-5 March. Signals from it continued to be received until it had receded to some 400,000 miles and had entered an orbit round the Sun, so becoming a tiny artificial planet. That, for the moment, ended the series, but meanwhile the Russians had been far from idle; during 1959 they launched their three celebrated Luniks, the second of which landed on the Moon, while the third went on a 'round trip' and sent back photographs of the area of the lunar surface always turned away from Earth.

It was not until 1961 that the Americans were ready to try again. The Ranger programme was initiated on 23 August, but the first two vehicles failed to go anywhere near the Moon. Ranger III, launched on 26 January 1962, seemed much more promising, and for a while hopes ran high; it looked as though the attempt to photograph the Moon from close quarters would be crowned with success. Unfortunately, errors then became apparent. The first stage of the launcher, an Atlas rocket, had been slightly too effective, so that the vehicle moved at more than its planned velocity and never approached the Moon to within less than 23,000 miles. Even so, it was still hoped that photographs would be received, and Ranger III was positioned by remote control, but the ill-luck was still there; further faults developed, so that only the extreme edges of the television pictures could be picked up, showing no details whatsoever.

The story was continued in April, with Ranger IV. The vehicle is thought to have reached the Moon on 26 April, but this time the photographic equipment failed as well as the guidance system, so that no data of any sort were obtained. Ranger V, of 18 October, was even less successful; it missed the Moon by a wide margin, and contact with it was lost at a relatively early stage.

The next attempt came from Russia. On 2 April 1963 the Soviet space-researchers launched Lunik IV, which was said to weigh over 1 1/4 tons and to carry complex equipment. Very few details about it were released, and even now nobody outside the USSR scientific circle seems to know just what it was meant to do. In the event, it merely went past the Moon and continued its journey into space, so that it was clearly a failure.

When 1964 opened, the situation appeared somewhat depressing; all in all, very little obvious progress had been made for four years so far as moon-shots were concerned. I think that the news of the launching of Ranger VI, on 29 January, was received with resigned pessimism - and the fears were justified. At least the Americans brought the vehicle down exactly where they had hoped, in the Mare Tranquillitatis, but the photographic equipment failed completely. Neither has any trace of an impact-scar been detected, though the exact position of the landing is known.

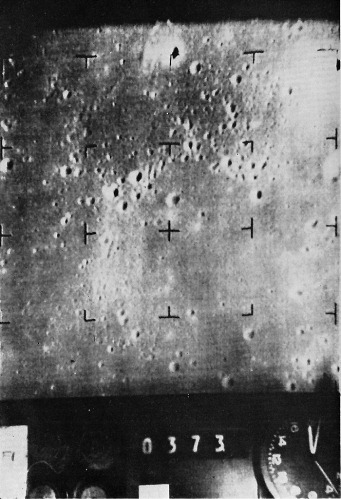

Photographs of the Moon taken from Ranger VII

Left: The moon from 34 miles the area covered is 16 miles square. Right the Moon from 3 miles; takes 3.2 seconds before Ranger VII hit the Moon.

With the ascent of Ranger VII, on 28 July, the total bill for the American lunar programme passed the £90,000,000 mark, and so far there had been remarkably little to show for it. Yet somehow or other there was a feeling that the new launching would be different - and so it proved.

Ranger VII took 67 hours 35 minutes to complete its journey of 243,665 miles. There were no communication troubles; the probe was tracked from America and also from Jodrell Bank, though the last stages of the flight could not be followed from Britain because the Moon had dropped below the horizon. When the vehicle was some 1,300 miles above the lunar surface, the cameras were turned on, and for the next 16minutes worked perfectly; 4,316 pictures were received, the last of which was still being transmitted when Ranger VII smashed itself to pieces on the Sea of Clouds.

There have been reports that on this occasion the impact was actually observed. Astronomers at Gape Kennedy, using powerful equipment, described a small black speck about twenty seconds after the crash-landing; this speck mushroomed into a small white cloud 'resembling a three-leaf clover', which rapidly diffused and disappeared. The reports are not conclusive, but they are at least plausible. Whether any permanent scar will be detected seems rather doubtful. If it is visible at all, a giant telescope will be needed to show it.

Before going into further details about the photographs themselves, it is important to say something about their purpose. It would be pointless to spend over £90m. in doing no more than show fine details on the Moon unless they would add materially to our knowledge of the lunar world, but in fact there were several urgent problems which could not be solved in any other way. The main question concerned the nature of the surface layer.

In 1955 a revolutionary paper had been published by T. Gold, well known for his work in helping to formulate the steady-state theory of the universe. According to Gold, the lunar craters were produced by meteoritic bombardment, while the maria were filled with dust - so that any astronaut unwise enough to land there would be comprehensively swallowed up in a dust-ocean more treacherous than any quicksand. Practical lunar observers were, in general, unimpressed,* but the theory could not be rejected out of hand, and it had to be checked before the more ambitious programmes, involving manned craft, could be worked out in every detail.

Another point concerned the numbers of very small craters scattered over the Moon. From Earth, it is difficult to see any crater with a diameter of less than 1,600 feet or so; in fact, we can examine only the coarser details. It was essential to find out whether any truly level ground existed, or whether the surface were pitted even in those regions which seem smooth and mirror like in Earth-based telescopes. For this reason, Ranger VII was aimed at a mare-surface rather than a bright upland area. It came down in the Mare Nubium, in the general neighbourhood of the low-walled, 36-mile crater Guericke - and the aiming was incredibly precise. A mid-course correction was made, on schedule, but no terminal correction was necessary.

Of the first pictures to be made available, two were particularly informative. From an altitude of 3 miles, 3.2 seconds before impact, craters less than a dozen feet across are shown; the last picture, still being transmitted at the moment of landing, covers an area comparable with that of a tennis-court, with craters 3 feet across and a mere 12 inches or so deep. These tiny objects are sharp and clear-cut, which would be out of the question in a surface of soft dust. Moreover, it was stated that some of the other photographs showed rather larger craters (that is to say, over 100 feet in diameter) containing isolated rocks which had been presumably hurled out during the formation of still larger craters — and yet were obviously not dust-covered. In fact, Gold's whole idea was wrong. Any dusty or ashy layer on the Moon could hardly be more than a few inches deep, so that basically the surface would be strong enough to bear the weight of a landing vehicle, even if unsafe areas existed here and there.

Associated with the dust problem was the old, much-discussed argument about meteors versus volcanism as the main force in crater production. Gold had been a strong supporter of the impact theory, and so had many other professional astronomers, such as G. P. Kuiper, H. Urey and F. Hoyle. Urey had even stated that the evidence was so overwhelming that there was no need to talk about it further. Others were not so sure, and at the New York lunar conference held in May 1964, at which I read a paper, I found that the meteor idea had come under heavy fire from geologists as well as practical lunar observers. For instance, J. Green of the United States and G. J. H. McCall of Australia drew attention to a possible analogy between lunar craters and terrestrial volcanic calderas. My own views were quite clear-cut; as I said at the conference, I have always been an 'unrepentant vulcanist', though no doubt numerous small meteor pits exist.

It cannot be said that the Ranger VII pictures give a final answer, but it looks very much as though vulcanism has, after all, been the main factor. At any rate, there can be no doubt that the Moon has been the site of tremendous volcanic activity at some stage in its history. Many of the minor pits in the area where Ranger landed may well be due to impact - but in all probability the bodies producing the pits were hurled out from lunar craters of greater size instead of coming from space.

One photograph, taken from a height of 34 miles, showed what Kuiper called 'a whole nest' of small craters, some of them no more than 15 feet in diameter, said to have rounded crests potentially dangerous to astronauts. This particular area was crossed by one of the bright rays from the 56-mile crater Copernicus, and it was evident that some connection existed between the craterlets and the ray, so that the craterlets looked as though they must be secondary pits due to the eruption of Copernicus itself. As for the rays, it was claimed that they were sizeable rocks thrown off during the production of the focal craters - but to me this idea does not seem to be at all convincing, and the rays remain enigmatical.

Moreover, there is at least a chance that some of the rays shown in the photographs do not come from Copernicus at all, but from Tycho. Of course, Tycho, in the southern uplands of the Moon, is a long way from the point where Ranger VII landed — but the Tycho ray-system is more extensive than that of Copernicus and the alignment seems to fit the general Tycho pattern well. Further studies of the photographs will certainly clear up this and other points. Meanwhile, Ranger VII has at least disproved the dust-drift theory, and it now seems likely that the mare surfaces are made up of some material such as hardened lava.

Of course, only a very limited part of the Moon was covered; even the first pictures, taken about i6| minutes before impact, showed an area of no more than 180,000 square miles, appreciably less than that of France. Really level ground was lacking, and it does not seem probable that other mare-surfaces are much smoother; astronauts of the future cannot hope to find any mirror-like expanses big enough to be pressed into service as landing-grounds.

It cannot be said that the photographs have provided any major shocks for those astronomers who have always disbelieved in Gold's dust theory, and who have regarded the lunar surface as essentially volcanic in character. However, it has been pointed out that there seem to be few small cracks or fissures. Fissures of such a kind may be absent, or else they may simply not have shown up; this is a problem for the future, but since there are so many crater-chains, clefts and valleys on a larger scale, it would be distinctly strange to find that small cracks do not exist.

There is one more point which has already been brought up, though not by the American scientists concerned in the experiment. It has long been thought that the Moon is utterly without life; even lowly vegetation is improbable to the highest degree. The Ranger photographs have shown nothing that could be interpreted as being due to living organisms, and nobody had had the slightest expectation that they would. The Moon is a sterile world, and probably has always been so.

The success of Ranger VII means that plans for the future can be continued with high hopes. Two more vehicles of the same sort are planned for early 1965; Ranger VIII will go up in January, all being well, and Ranger IX will follow in February. No major modifications to the probes or launchers are expected, but different areas of the Moon will come under study, and it may well be that one of the rockets will be aimed at a bright upland instead of a dark plain. I rather hope that one Ranger will land near Aristarchus, the brilliant crater near which observers at the Lowell Observatory, Flagstaff, reported red patches in October and November of 1963.

This will complete the Ranger series. Next will come vehicles of the Surveyor type, involving soft landings, and 1966 should see the launching of Orbiter vehicles, which will go round the Moon taking high-resolution photographs from heights of 30 miles or so. Whether the Americans will manage a manned flight to the Moon before 1970 remains to be seen. Incidentally, we must not forget the Russians, who have had no real successes with their lunar or planetary probes since 1959, but who are certainly making plans of their own. A soft landing on the Moon by a Soviet space-craft may be imminent.

At present Ranger VII lies wrecked in the Mare Nubium, but I doubt whether it will stay there for ever. At some future date an expedition from Earth will surely collect its shattered remnants and carry them off to a museum. America's lunar probe accomplished its task more brilliantly than its makers can have dared to hope, and it has certainly earned its place in history.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for commenting on our website, remember, No Sex adds please -- were British !!