Over the years, I have been referred to many times as 'an astrologer'. There are still some people who confuse astrology with astronomy, and after much deliberation we decided to give a programme to the subject, prompted by the fact that at that time three planets {Mars, Uranus and Pluto) were all in the constellation of Leo.

The results were, predictably, somewhat explosive. Letters from infuriated astrologers poured in; they ranged from organizers of 'colleges' providing 'degrees' in astrology {at a suitable fee, of course) to one earnest viewer who wrote saying that as I appeared on the television screen, my aura was dull yellow and speckled. All I could do in the latter case was to write back assuring the correspondent that I would do my best to have my aura dry-cleaned before the next programme. There were also letters from flying saucer enthusiasts and followers of the Atlantis cult. I spent many hours battling with the deluge of mail, though with regard to the 'colleges' I admit that I merely put them in touch with each other and took no further action.

The most interesting point about it all was that not one of the astrologers offered any answer to the objections I had put forward. And there were, of course, many letters too from people who were glad that I had pointed out the difference between astronomical science and 'what the stars foretell'.

At the present moment Mars is still a prominent feature of the evening sky. Though it is receding from the Earth, it is still much brighter than any of the stars near it, and its strong red colour marks it out at once. During early April binoculars or low-power telescopes show another planet close beside it; this is Uranus, the third of the remote gas-giants, much larger than either Earth or Mars, but so distant that it is never easy to see with the naked eye. A moderate telescope is enough to show its rather dim, greenish disk, though larger instruments are needed to reveal any of its five satellites.

Uranus lies far beyond Mars, and is in fact very much farther from Mars-than we are. The two planets appear close together simply because they happen to lie in more or less the same line of sight. Both are in the constellation of Leo the Lion - and yet this, too, is merely a conventional means of expression, since even the nearest star is immensely more distant than a planet.

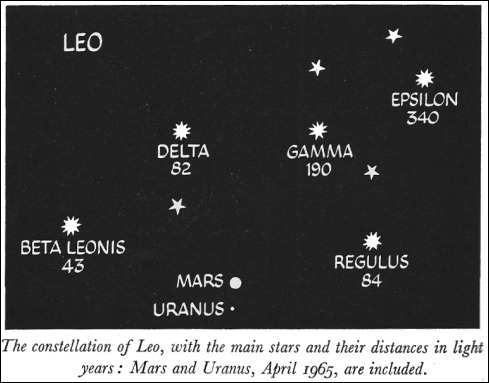

The diagram shows what is meant. The main stars of Leo are shown, together with their distances in light-years. (A light-year, or the distance travelled by light in a period of one year, is equal to rather less than six million million miles.) The curved line of stars which includes Regulus, Gamma, and Epsilon is generally nicknamed 'the Sickle'. Mars, at the moment, is only about 75,000,000 miles away - that is to say, less than seven light-minutes!

To say that Mars is 'in' Leo is therefore decidedly misleading. .After all, a sparrow flying at rooftop-height against a background of clouds is not 'in' the clouds.

There is the further point that the stars of Leo are themselves totally unconnected with each other. Epsilon Leonis is over 250 light-years away from Regulus, which is considerably more than the eighty-four light-years separating Regulus and the Sun. The pattern of the constellation is nothing more than a line of sight effect, and if the Solar System lay in a different direction the stars of Leo might well be spread out all over the sky. In fact, a 'constellation' is not truly a constellation at all.

Yet these constellation groups, and the apparent positions of the planets in the sky, form the whole basis of the pseudo-science of astrology, which was widely studied in mediaeval times and which is still taken quite seriously in a few countries, notably India. It was claimed that a person's whole character and destiny was influenced by the positions of the Sun, Moon, and planets against the stars at the moment of birth, and an astrological horoscope was regarded as a most important document. Famous scientists of past times were believers in astrology; even Johannes Kepler, who laid down the famous Laws of Planetary Motion, cast horoscopes (though whether he believed in them is another matter), while the great Sir Isaac Newton was most decidedly a mystic. Still earlier, astrology was thought to be just as important as true astronomy.

Originally the Earth was thought to be flat, and to lie at the centre of the universe. The old Greek philosophers realized that the Earth is a globe, but only a few of them were bold enough to suggest that our world might move round the Sun; indeed, it was not until the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that the idea of a Sun-centred system became firmly established. Astrology, then, is related entirely to the Earth as a centre.

The mediaeval astrologer was a most influential person. He cast horoscopes for kings and princes, he made weighty pronouncements, and sometimes he even predicted the approaching end of the world. Comets were regarded as particularly unlucky, but, according to the astrologers, conjunctions of several planets were even worse.

It is natural that the planets - or some of them - should at times appear close together in the sky; as we have seen, Mars and Uranus are at present only a few degrees apart. But when several bright planets met in the same constellation, in 1524, a famous German astrologer named Stoeffler took the opportunity to forecast the end of the world, and caused widespread panic; people even went so far as to build boats and arks so as to escape the expected flood. Much more recently, in 1962, five planets were together in the constellation of Capricorns (the Sea-Goat), and once again the astrologers were much alarmed. In India, particularly, there was great relief when the planets spread out among the constellations once more and the world still survived.

The Sun, Moon, and planets are confined to a certain region of the sky, known as the Zodiac. This is because the orbits of the planets, including the Earth, lie in much the same plane; the inclination is seven degrees for Mercury and less for the remaining planets. There is, however, one exception: Pluto, which is a relatively faint telescopic object, and was not discovered until 1930. (At present it, like Mars and Uranus, will be found in Leo.) The inclination of Pluto's orbit amounts to seventeen degrees, so that it can leave the Zodiac. This is unlikely to worry the astrologers, and in any case the 'signs' of the Zodiac no longer correspond to the actual constellations, since the effects of precession - that is to say, the slight wobbling of the direction of the Earth's axis - have become quite appreciable since classical times. The vernal equinox, or point where the ecliptic cuts the celestial equator, is still known as the First Point of Aries, but by now it has moved out of Aries (the Ram) into the neighbouring constellation of Pisces (the Fishes).

Two of the other planets, Uranus and Neptune, were also unknown to the old astrologers; Uranus was discovered in 1781. Neptune in 1846. If these planets do in fact exert an influence upon human destinies, it would be interesting to learn why the astrologers did not track them down long before the astronomers could do so with their telescopes! There are also the numerous minor planets, or asteroids, which move round the Sun between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. It is true that they are small in size, but quite a number of them are brighter in our skies than remote Pluto. One of the asteroids, Vesta, is even visible with the naked eye when best placed, whereas Neptune and Pluto, among die 'proper' planets, are always far below naked-eye visibility.

One of the biggest absurdities of astrology lies in the names of die Zodiacal constellations themselves. The familiar groups, such as Leo, Taurus (the Bull) and Gemini (the Twins) are of ancient origin, though it is worth noting that the Chinese and the Egyptians used a completely different system. Nobody is quite sure in which country our own constellations were first described. The old Ghaldcean star-gazers may have been responsible; astronomers in the island of Crete have also been suggested. In any case, Ptolemy, last of the great scientists of ancient times, listed forty- eight constellations in his catalogue of the stars. Ptolemy died about a.d. 180; even then, the patterns were very old indeed.

Yet few of the constellations bear the slightest resemblance in outline to the objects after which they are named. It requires considerable imagination to make a bull out of Taurus, a lion out of Leo, or a crab out of Cancer. Moreover, many of the names are mythological; Leo commemorates the Nemaean lion killed by the hero Hercules during his twelve labours. (Hercules is also in the sky, but he is not in the Zodiac, and is much less brilliant than his leonine victim.)

What was evidently done was to draw up arbitrary figures bearing little or no relation to the star-patterns concerned, and then allot names. When this had been done, the astrologers assigned 'characteristics' to the constellations according to the names that had been given. Cancer, the Crab, is said to be a watery sign. Leo, of course, is virile and positive; it is said that the Sun is at its greatest astrological strength when in Leo.

Altogether, the whole procedure seems to be an excellent case of reasoning round in a circle, and it is hard to understand how any thinking person can take it seriously. It is hardly rational to take a collection of totally unrelated stars, make some sort of a figure out of the pattern, give it a name and then claim real significance for it. One can only echo the words of the Duke of Wellington when greeted in the street by a stranger with 'Mr Smith, I believe?' 'Sir - if you believe that, you will believe anything.'

Some astrological predictions come true. This is only to be expected; it would be most surprising if they did not, since they cover all sorts of subjects and are usually wrapped up in suitably nebulous language. Now and again some astrologer will achieve a lucky hit, which will be well publicized. The same is true of personal horoscopes, though for every correct statement there are always several which are very wide of the mark.

One typical case may be cited. Not long ago, an astrological magazine forecast the sudden death of President Kennedy, and gave the correct month of the assassination. This prediction was regarded as a convincing justification of astrology - but it must also be related that during the previous three years the same magazine had foretold the death of President de Gaulle, the deposition of General Franco, and the removal of Dr Salazar of Portugal. It is worth noting, too, that in 1938 and 1939 British astrologers were as emphatic as they were unanimous: there would be no war against Nazi Germany.

Only the credulous will believe that line-of-sight effects 0: planets and stars will have any effect upon a man's character or life, but it is nevertheless illuminating to ask a serious astrologer just how these alleged influences occur. I did ask precisely this question of an astrologer a few months ago. His reply was: hasn’t the slightest idea.' This was, at least, a straightforward admission, and differed from the usual attitude. Most astrologer; faced with such a query, would have started talking about mysticism, ancient teachings, and, of course, vibrations. The latter word is a favourite of all devotees of what may be termed the 'fringe' of science; it is also very convenient, because in such a context it may be taken to mean practically anything.

Arguments which have no basis of common sense are always hard to refute. It is so with astrology, which lacks any scientific or logical foundation, and which is a relic of the past, when superstition was rife and concrete knowledge was very limited. In ancient times, when the nature of the universe was not understood, it was natural enough to regard the Earth as of supreme importance, with the remaining bodies set in the sky merely for the sake of Earthmen; in such a climate, astrology could be expected to flourish. By now it has, of course, been completely discredited in Europe, though in the East it lingers on.

It is, after all, virtually harmless, and many people are amused to read the 'What the stars foretell' columns in the popular press. It must also be emphasized that professional and amateur astrologers are, in general, completely honest and sincere. They take themselves most seriously; they give each other 'degrees', they put impressive-looking letters after their names, and they offer instruction to the unenlighted, all with the best of intentions. The same can be said of other equally sincere bodies, such as the International Flat Earth Society, which still exists, and the German Society for Geophysical Research, whose members believe the world to be the inside of a hollow globe, with the Sun in the centre of the hollow and Australia situated somewhere above our heads.

There seems no need to say more. Astrology is not a science, and no person with any scientific background will take it seriously, but its name still leads to a certain amount of confusion. Suffice it to say that astrology and true astronomy are entirely different, and entirely unassociated. Yet the sincere astrologer does little damage, and, like the flat earther and the hollow-globe believer, he means well.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for commenting on our website, remember, No Sex adds please -- were British !!