In 1960 everyone in Western Europe was well aware of the Soviet achievements in space research; at that time the Russians were far ahead of the Americans in rocket techniques, though from all indications the gap has narrowed since (even if it still exists at all). What was not so generally known was that in the field of astronomy, too, the Russians were very much to the fore. When I was invited to visit the USSR, I had the opportunity to see for myself, and on my return I broadcast my impressions.

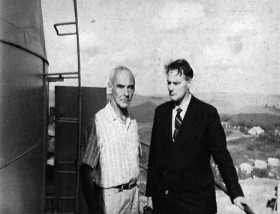

The Crimean Astrophysical Observatory, photographed by the author in 1960. Left the dome of the 102-inch reflector; construction was still not completed, and some of the scaffolding can be seen. The author shown with Dr Nikolai Kozirev outside the 102-in dome.

In October 1960 I accepted an official invitation to visit the USSR, and to deliver some lectures about the Moon. I stayed for a fortnight, during which time I went to three of the greatest observatories in European Russia and also met many of the astronomers whom I had previously known only by reputation and correspondence. The account which follows must necessarily have a personal slant, but will, I hope, serve to underline the remarkable progress made by Soviet astronomy during the last few decades.

I went first to Moscow, where the official headquarters of the USSR Academy of Sciences is to be found. One interesting function which I attended, and addressed, was an official celebration held in the 'House of Scientists' to mark the third anniversary of the launching of the first earth satellite, Sputnik I, on 4 October 1957 - a date which will certainly become historic. Two years later, on 4 October 1959, Lunik III began the flight which resulted in the successful photographing of the far side of the Moon. Among the speakers at this meeting was Professor Stanyukovich, who described the conditions which he expected would confront the first voyagers to land on the lunar surface. Throughout my stay in Russia I was deeply impressed with the quiet confidence of the space researchers; they at least have no doubt that manned, as well as unmanned, interplanetary travel will be achieved before very long.

Great interest is of course being shown in the Lunik pictures of the far side of the Moon, of which I saw over thirty in addition to the two which have been widely shown in Britain. These photographs have been used by Professor Y. N. Lipski to draw up a comprehensive chart of the new regions. Over 500 craters have been plotted, and it is clear that the hemisphere we normally never see is just as crowded as the areas familiar to us. The limb areas of the visible hemisphere of the Moon are naturally very foreshortened as seen from Earth, and are difficult to map. However, work in this field was undertaken by the Welsh selenographer H. P. Wilkins, who died last January, between 1910 and 1958. It was pleasing to hear from Lipski that he had found Wilkins' limb-area charts to be of the greatest use in correlating the Lunik photographs.

Moscow has a fine planetarium. It is run as an educational establishment, so that admission is free, and the programme is carried out with complete scientific integrity. There is indeed no need to dramatize astronomy, and the wisdom of the Soviet policy is shown by the fact that the Moscow planetarium has 3,000visitors daily. As well as the main dome, there is an impressive entrance hall containing many models (including the Soviet space- probes) and demonstrations, while the grounds include several small observatories. The policy is for the beginner to study the material in the entrance hall, then to see a display in the dome, and then - weather permitting - to go to one of the observatories and 'see for himself. The main projector, like most others all over the world, is a Zeiss. One of the more spectacular, though scientifically sound, features is the way in which the Moscow skyline round the display dome can be changed to a lunar landscape by the touch of a button. I used this projector myself during one of the public lectures which I gave there, and the effect was as realistic as is possible in view of our present state of knowledge.

While in Moscow I drove out to Zvenigorod, some kilometres away, to see one of the satellite-tracking stations. There are eight camera-telescopes, and it is not likely that any artificial probe which passes over Zvenigorod in clear weather will escape detection. Numerous other stations of this sort have been set up in the Soviet Union.

From Moscow I went to Leningrad. Here I saw the oldest observatory in Russia - the Chamber of Curiosities, founded by Peter the Great as a museum. According to tradition, Peter was anxious to create interest in the museum, and provided visitors with a cup of tea or a glass of vodka after they had examined the exhibits - which increased the attendance considerably! The observatory was set up at the top of the building, and was used by the first of Russia's great astronomers, Mikhail Lomonosov. However, it is no longer used as an observatory.

Leningrad is famous in the astronomical world as the home of Pulkovo Observatory, which lies not far beyond the city boundaries. Pulkovo has a long and honourable history, but the present equipment is entirely new. During the war, the front line of battle lay less than two kilometres away, and German shelling reduced the whole observatory to a mass of tangled wreckage; I saw photographs, taken in 1945, which reminded me of the worse-damaged parts of London. Nowadays, no trace of this destruction remains; everything has been rebuilt, and there are twenty-six optical telescopes as well as twelve radio telescopes. The largest optical telescope, a fine 26-inch refractor, is a Zeiss. It was made on Hitler's orders as a present for Mussolini. However, the war ended before the telescope could be finished, and the instrument was diverted to Pulkovo, where it is doing excellent work.

The relatively new Department of Planetary Physics at Pulkovo is headed by Dr A. B. Markov, one of the leading Soviet authorities on the Moon. Though the main emphasis at the observatory is on astrophysics and stellar astronomy, it is interesting to find that our nearest neighbours in space are not being neglected; this trend was noticeable, too, at the Crimean Observatory and elsewhere. It is at Pulkovo that Dr Tatiana Kochan, one of Russia's many talented women astronomers, is carrying out specialized investigations of the polarization of the light of the Moon.

The most striking characteristic of the radio astronomy department at Pulkovo is a 'rail' aerial made of ninety separate sheets; this has high resolution, and works at a wavelength of 2 to 5 centimetres. I did not see a great deal of Russian radio astronomy, and I am not myself a radio astronomer, but it may be true to say that in this science the Soviet workers have not advanced so far as those in Britain.

Leningrad too has an excellent planetarium, as popular as that in Moscow. In addition there is a smaller installation at the Palace of Pioneers in the city. This is very like the star-dome planetarium in the South Kensington Science Museum in London, and is amateur-built. It is most popular, particularly with the young enthusiasts.

Leningrad University has its own observatory, equipped with a g j-inch Glasenapp refractor and other instruments. Unfortunately, weather conditions are poor. During the summer, the skies do not become dark enough for stars to be seen; the famous Leningrad 'white nights' must be a serious handicap to astronomers, beautiful though they may be. When winter sets in, there is apt to be a great deal of cloud and fog. As Professor Sharonov, of the university, told me with regret, observing under reasonable conditions was generally possible only in March and October. This also applies to Pulkovo itself, and it is likely that in future large instruments will be confined to southern stations.

Sharonov is particularly interested in the planets, and is carrying out many interesting practical experiments. He is one of the few Soviet astronomers I met who are not convinced that the dark areas on Mars are due to vegetation; he considers it more probable that they are due to dust. Future research will doubtless clear the matter up, but meanwhile it remains a fascinating problem. Work will be continued this winter; Mars has now become prominent, shining in the south-east after dark, and will be at its brightest near the end of December, when it will be only 56,000,000 miles away.* My next visit was to the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory, near Simferopol in the south part of the USSR. This is primarily a solar station, and the Director, Dr Severny, is one of the world's most eminent solar physicists. While there, I was particularly glad to meet Dr N. A. Kozirev, who became well known in Britain two years ago when he reported the detection of an outbreak inside the lunar crater Alphonsus. Examination of the spectrograms taken on that occasion leaves no room for doubt that an outbreak did in fact occur, so that the Moon is not completely inert. Later activity (1959) is less definite, and Kozirev himself is not too certain of it. On that occasion I was observing from my own home, and was unable to confirm anything unusual; but Kozirev told me that he himself had made no visual observations of the suggested disturbance, so that my own failure was hardly surprising.

The 50-inch Zeiss reflector, used by Kozirev for his lunar and planetary work (though its main function is, of course, astrophysical), is a fine instrument, but will be overshadowed by the new 102-inch reflector which has been set up in a dome nearby. The telescope is the largest in Europe and the third largest in the world. During my stay in the Crimea the dome was in its last stages of completion, and there were workmen everywhere. The telescope itself is ready - indeed, by now the whole equipment is in operation - and is a skeleton tube, with a mounting not unlike that of the Palomar 200-inch reflector in California. As well as its main work, on stellar and galaxy research, it will be used for lunar and planetary investigations, and Kozirev, together with the Director, is busy planning new auxiliary equipment for it in this field.

From the outside of the 102-inch dome one has a superb view of the whole observatory, which, incidentally, is built on the site of a village which flourished about 700-600 b.c. Various interesting remains have been found, including a large urn of Greek type. At present, preparations are being made for the total solar eclipse of next February, when the track of totality will pass straight through the observatory. It will be many years before this happens again, and it is greatly to be hoped that the skies will be clear at the vital moment.

I also had the latest news about the 236-inch reflector which will surpass even the Palomar giant. Work on it is going well, and it is expected that the telescope will be ready in six or seven years. The optical equipment is being made in Leningrad. The reflector will not be set up in the Crimea; after sending expeditions to all parts of the Soviet Union, it has been decided that a site in Asia will give the best conditions. No doubt this great reflector will play a principal role in astronomical research.

In general, I was struck by the wide interest shown in astronomy, as well as astronautics, by everyone I met. The young people are both enthusiastic and knowledgeable, and Professor Sharonov told me that about 50,000 astronomy students pass through the universities each year. Every encouragement is given, and there are also many amateur societies. Even a very brief visit, such as mine, is enough to show that astronomy in the USSR is in a most flourishing state *, and that many important developments may be expected within the next few years. Neither must I refrain from commenting upon the extreme friendliness and courtesy which was extended to me throughout my stay in the Soviet Union.

*In fact, they were clear. I carried out a television commentary from the top of a mountain in Jugoslavia!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for commenting on our website, remember, No Sex adds please -- were British !!